The following is an excerpt from Kaufman Global’s White Paper: Engage the Organization and a Performance Culture Will Follow. Here we examine the reasons why leaders fail to pursue employee engagement, even while it’s proven to be fundamental to success.

Employee Engagement: Why Do Leaders Fail to Act?

If we accept the idea that a fully engaged organization is fundamental to success, then we must ask, “Why Do Leaders Fail to Act?” The simple answer may be because it is exceedingly difficult to challenge ingrained culture and belief systems. Pushing decisions down, engaging the organization broadly and deeply, and giving up some amount of control is not a simple matter. In fact, it counters the culture of traditionally run organizations.

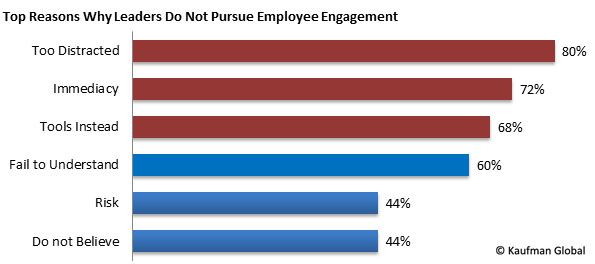

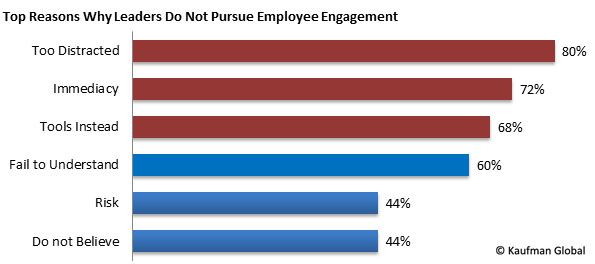

To dig a little deeper into the reasons leaders fail to pursue engagement, Kaufman Global recently surveyed a large group of top leaders and known change agents. These individuals come from diverse industry backgrounds, such as consumer products, energy, government and technology. Averaging over 20 years of experience, each has a proven track record of successfully engaging and improving their organizations.

6 Reasons Employee Engagement is So Difficult

- Too distracted to do anything new

- Immediacy – This is the “tyranny of the emergency”

- Tools Instead – The belief that workshops and Rapid Improvement Events (RIE) solve employee engagement

- Failure to understand how real engagement works

- Risk – It’s simply one more thing that inhibits more immediate results

- Do not believe it makes a difference.

Each of these are described below.

The question was asked, “If we accept that the leader’s function is to create value and that one vital and comprehensive way to do this is by fully engaging the organization — at all levels and at all times — why do so few leaders truly, actively pursue this essential aspect of sustainability and performance?” Six possible answers were given with a rating that ranged from 1 (seldom) to 5 (often). A summary of the results follow. Additional detail is provided within the white paper.

Distraction | The top reason at 80% is that leaders are too distracted with day-to-day operations and other external inputs to focus themselves or their teams on anything other than existing systems applied to here-and-now deliverables. This defines a mostly reactive environment and one that has multiple competing inputs — often from above. It’s true enough that “Change starts at the top.” With enough distraction the opposite is just as true (and way more common). In this instance, engaging the organization is not valued enough to make it a formal priority.

Immediacy | Next comes immediacy at 72%. Immediacy has to do with the extreme focus on short-term goals and results. There’s no time for something that might not deliver a here-and-now win, requires some level of faith and is even slightly different than anything already being done. Moving upward in the organization, if results are not achieved, personal compensation and job security are at risk.

Immediacy and distraction are intimately linked. Distractions mount as the need for immediate results rises. Two back-to-back quarters of poor performance and the level of distraction goes off the scale. If this cycle goes on long enough, pressure and confusion over priorities lead to loss of morale and disengagement. People tend to exit these types of environments, and it’s unfortunate that engagement — a major mitigation factor and the single greatest contributor to employee morale and retention — is among the first to go and is seldom pursued in a systematic fashion.

Tools | Following closely at 68% is “toolitis.” This is a common ailment of many organizations where things like Kaizen Events, Value Stream Mapping and 5S are viewed as engaging the organization. It’s true that these types of activities get people involved, but only temporarily. Six Sigma is more of an expert practitioner methodology and has even less of an engagement mandate. There are many examples of organizations stalling in their Continuous Improvement efforts when they apply a tools-only approach. They have the tools, but value workers are not compelled to pick them up and use them because they aren’t immediately aware of, or have visibility to, their own performance. “Toolitis” is a big problem within production organizations, where employees find it difficult to expand into business processes because they can’t translate the improvement techniques they started with. Tools are most effective when they held in place with engagement.

All of these factors are closely related and combine to form a powerful barrier to real change. That “fail to understand” and “don’t believe” were scored as significant factors says a lot ― and not in a good way ― about basic leadership and management skills. Training is one element that can help, but people learn through their own experiences that are illuminated by existing values and norms. To change these patterns requires a significant reset on how organizations reward certain behaviors.

These barriers — and they apply at all levels — are daunting for anyone attempting change within the area they control. Some traps are more common depending on where you are in the organization. The lower you go, the more the system will attempt to kill your initiative (i.e., “Not invented here.”, “Who else knows about this?” or “This is not part of your job description.”). As you go higher in the organization, the problems associated with trying anything different prevent ignition ― pick any combination of reasons.

Those in the middle of the organization have simultaneously the most to gain and the most to lose. Here there is a lot of local control over value creation ― therefore the gains can be fast and big. In addition, the personal risk of failure for trying something different is less; yet there is strong attachment to the status quo and disruption isn’t much welcomed. Besides, in many situations, operating marginally better than one’s peers doesn’t require anything as foreign as attempting your own fully engaged organization. Without the support of peers and bosses, mid-level managers quickly start to feel they are rowing upstream alone.

Given all the barriers, it’s amazing that anyone pursues the engagement prerogative, but some do. And when someone, somewhere intends to make a meaningful difference by getting everyone involved to the fullest extent possible, the journey can be made a little easier with well-conceived boundaries that are defined by accountabilities, expectations and metrics. Journeys begin by starting to think about engagement as a process (as opposed to an outcome)…

Ready to dig deeper? This article is continued in our White Paper: Engage the Organization and a Performance Culture Will Follow Click here to download the full text.

Drop us a line if you want to learn more about Kaufman Global’s view on engagement.

When it comes to guiding an organization through transformative change, control is the determining factor. How much design and direction is pushed down from the top and how much discretion is left to the rest of the organization will make or break any initiative. The best outcomes are achieved by striking the right balance between two approaches: Top-down command and control versus autonomous decision making. Moving the organization off their status quo means certain things must be directed and enforced, yet many organizations fail because so much of their energy is focused on controlling the wrong things.

When it comes to guiding an organization through transformative change, control is the determining factor. How much design and direction is pushed down from the top and how much discretion is left to the rest of the organization will make or break any initiative. The best outcomes are achieved by striking the right balance between two approaches: Top-down command and control versus autonomous decision making. Moving the organization off their status quo means certain things must be directed and enforced, yet many organizations fail because so much of their energy is focused on controlling the wrong things.