World-Class Performance and the 20 Keys

The 20 Keys are a powerful method for first assessing current state performance in operations, and then developing an action plan for improvement to achieve world-class performance.

What is World-class?

world–class

adjective

: among the best in the world

: being of the highest caliber in the world <a world–class athlete>

Source: Webster-Merriam.com dictionary

What does the phrase “world-class” really mean? This question has been asked since the term first became popular in the 1950s. Companies that are considered to be world-class consistently exceed customer expectations. This type of performance isn’t accidental. It requires systems that adapt to dynamic environments. Kaufman Global frequently uses the 20 Keys system in our work with clients that are pursuing world-class performance.

The 20 Keys Help Organizations Focus

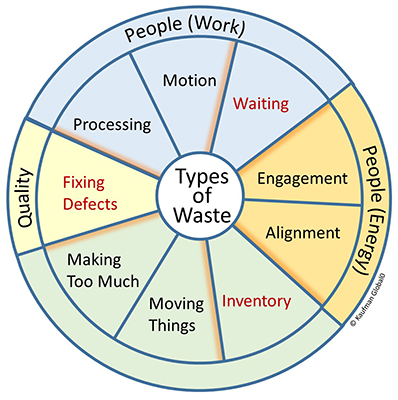

Lean is an important element in the pursuit of world-class. The simplest definition of Lean is: “The relentless pursuit of waste elimination.” Regardless of business type or industry, many companies have great success with their Lean efforts. Unfortunately countless others don’t. Maybe this is because there are so many opportunities to eliminate waste that it’s easy to get distracted, lose focus and wander off course. This isn’t a new problem. Decades ago Iwao Kobayashi at Toyota evaluated manufacturing companies that were considered to be world-class and identified crucial areas that must be addressed in order to achieve such status. He categorized these areas and put them into a framework called the 20 Keys.

Kobayashi’s original Keys addressed an entire manufacturing facility. Kaufman Global expanded the concept by developing sets of 20 Keys for many functions such as Healthcare, Engineering, Supply Chain, and Finance, among others. We then integrated the technique into our Lean Daily Management System® (LDMS®) methodology so that measurement takes place at the work group level.

The Kaufman Global 20 Keys® methodology:

- Is a continuous improvement mechanism that combines intuitive world-class definitions with a means of measuring and scoring group performance

- Focuses intact teams on the issues that affect their work

- Can be implemented and linked across the organization to provide a comprehensive evaluation of effectiveness

Strategy and Tactics

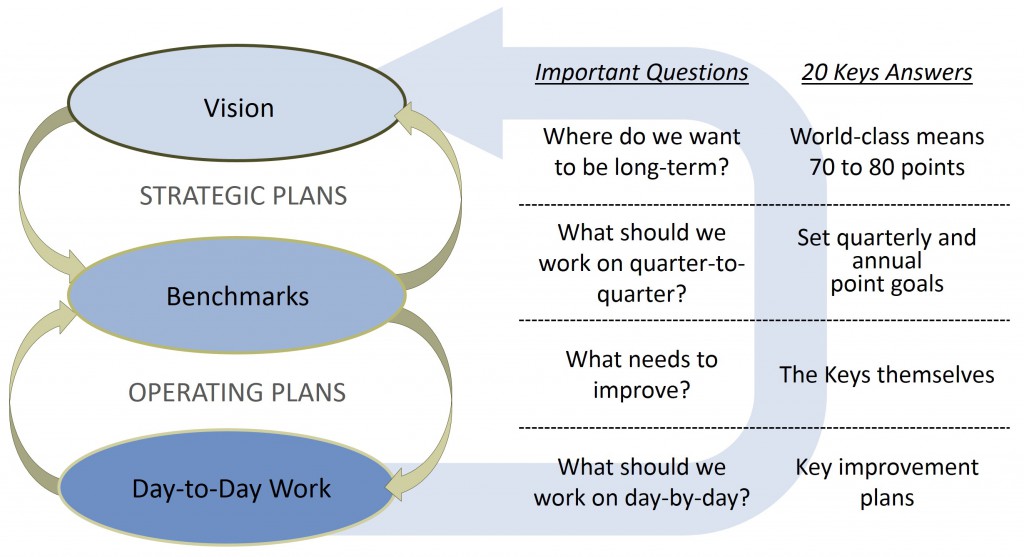

At first glance, the 20 Keys may seem like another audit technique. But when this powerful system is deployed inside the Lean Daily Management System, it enables work groups to take increased ownership of their daily work. As an added benefit, these highly relevant, local improvement efforts can be rolled up into organization-wide results by providing a common measurement system amongst multiple locations. The graphic below shows how the 20 Keys works both strategically and tactically, linking the big picture goals of leadership to improvements in day-to-day work. The 20 Keys takes an organization’s vision of world-class and:

- Connects the vision to actions by breaking it down into manageable pieces

- Provides an easy to understand and manage measurement system for progress toward the vision

- Enables relevant improvement plans close to the issues

Work group Application

Once the vision and strategic priorities of the organization are set, intact work groups complete a 20 Keys assessment and planning cycle to baseline their performance. Each key is evaluated at five levels of performance, ranging from 1 (Traditional) thru 5 (Best-in-Class). There are no ½ points and all statements or requirements must be met in order to achieve a given performance level.

With the baseline score established, the team selects their initial improvement keys and goals and creates a plan to achieve the gains. For example, if Safety was one of the keys identified for improvement and the current level of Performance was a 3, the team would be meeting the following definition:

- Safety – Level 3: The concept of unsafe behavior is well understood and associates are familiar with the specific unsafe behaviors that create hazards and / or accidents in their area.

To improve their score and achieve the next level performance, the team would need to establish new work rules and processes that ensure all Level 4 criteria were consistently met:

- Safety – Level 4: Unsafe behaviors are audited weekly and the results are posted. The team strives to eliminate root causes of unsafe situations and it is accepted practice for associates to coach each other on safe behaviors.

Regardless of whether the team sets an annual improvement goal of 10 points, or a quarterly goal of three points, it is important that they assess their performance against the plan at least every three months to ensure the action plan is being implemented and progress sustained. Posting the 20 Keys scorecard and implementation plan in the work area on the primary visual display enhances visibility to improvement progress and is a best practice.

Building the Foundation for World-class

World-class levels of performance are not achieved by accident, but through the execution of an incremental and strategic implementation plan. Kaufman Global has helped many organizations implement the 20 Keys and focus their improvement efforts. If you’ve already established a good foundation of continuous improvement, or even if you’re just starting the journey, the 20 Keys is a good way to enhance results and sustain momentum.

**********

To learn more about how to apply the 20 Keys and achieve world-class levels of performance, click here to download our Evaluating Continuous Improvement Effectiveness with the 20 Keys white paper.

The 20 Keys are part of Kaufman Global’s Lean Daily Management System ®.

The 20 Keys are discussed in this article: The Missing Link of Lean Success.

A solid transformation does not happen incrementally. Instead, it happens dramatically and visibly. Incremental enhancements to operations are Continuous Improvement (CI) efforts, which are crucial to be truly competitive but happen at a slower pace. In situations where bit-by-bit simply isn’t cutting it, organizations should consider real transformation. Only then will dramatic results be achieved through bold change and decisive action.

A solid transformation does not happen incrementally. Instead, it happens dramatically and visibly. Incremental enhancements to operations are Continuous Improvement (CI) efforts, which are crucial to be truly competitive but happen at a slower pace. In situations where bit-by-bit simply isn’t cutting it, organizations should consider real transformation. Only then will dramatic results be achieved through bold change and decisive action. As the team began calculating the cost savings of the new process, an “ah ha” moment occurred. The Director of Sales jumped up and said, “Wait, we are looking at this all wrong. What we have really done is create an opportunity for all of our sales representatives ― in every territory ― to spend an additional 10% of their time meeting with prospective customers. This has the potential to grow the company’s bottom line far more than cost reductions. Let’s project the value of that growth and go for it!”

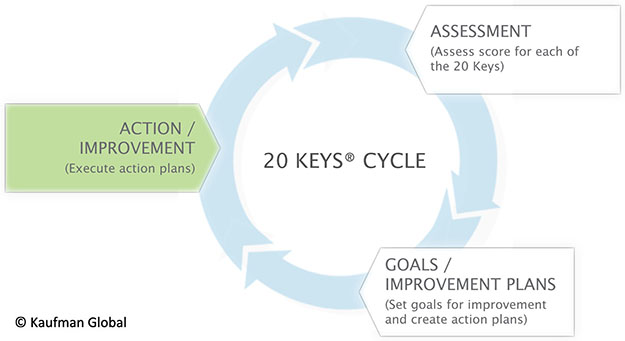

As the team began calculating the cost savings of the new process, an “ah ha” moment occurred. The Director of Sales jumped up and said, “Wait, we are looking at this all wrong. What we have really done is create an opportunity for all of our sales representatives ― in every territory ― to spend an additional 10% of their time meeting with prospective customers. This has the potential to grow the company’s bottom line far more than cost reductions. Let’s project the value of that growth and go for it!” As identified in the 20 Keys Cycle illustration above, the method drives a continuous cycle of improvement and builds on prior efforts. Typically repeated four times per year, location leadership or a designated representative works with the workgroup to assess their score for each of the 20 keys. This is an honest, direct exchange in which the they score each key against known criteria. Once the assessment is done, this same workgroup decides on which key(s) they should focus on improving. The objective is for them to increase their overall score by 10 points per year.

As identified in the 20 Keys Cycle illustration above, the method drives a continuous cycle of improvement and builds on prior efforts. Typically repeated four times per year, location leadership or a designated representative works with the workgroup to assess their score for each of the 20 keys. This is an honest, direct exchange in which the they score each key against known criteria. Once the assessment is done, this same workgroup decides on which key(s) they should focus on improving. The objective is for them to increase their overall score by 10 points per year.