Procedural Adherence and process discipline are achievable – but only when they’re treated as behaviors instead of tasks.

**********

Almost never do people violate procedures with bad intent. When it happens, it is enabled by a vague work culture coupled with urgent product and service demands. The effects of rules broken ripple through the organization with a range of negative consequences: personal safety, financial results, employee morale and public perception. Learn how to reduce procedural adherence problems and boost performance with behaviors that influence how employees view and deal with risk.

Almost never do people violate procedures with bad intent. When it happens, it is enabled by a vague work culture coupled with urgent product and service demands. The effects of rules broken ripple through the organization with a range of negative consequences: personal safety, financial results, employee morale and public perception. Learn how to reduce procedural adherence problems and boost performance with behaviors that influence how employees view and deal with risk.

The enterprise works hard to define and defend organizational procedures to maximize speed, accuracy and return — and still, rules are routinely broken. Individuals and teams opt for apparent shortcuts that appear to speed things up, but instead delay progress, sink performance or worse: put people in harm’s way.

Could it be that employees are wired to break the rules? With certain cultural ques; yes.

People view and manage risk at a personal level. This sometimes results in actions that oppose the stated values of the enterprise which include adherence to procedures and rule-following. But there is a contradiction here. Instead of diligent procedural adherence, the enterprise is often more concerned with chasing (perceived) fast results and near-term profit at any cost.

The translation: The true value of the enterprise is that it is actually ok to break rules, especially when a customer-facing issue or revenue stream is in play. From the point of view of the individual faced with the pressure of “getting the job done” it’s simply less risky to violate some procedures to keep the machine moving. This fundamental misalignment of values is a breeding ground for mistakes and ultimate poor performance – including and perhaps especially, catastrophic events.

Achieving a state of better procedural adherence — that is, predictably getting employees to stick to predefined processes and standards — is a losing battle for many organizations. They desperately want people to follow the rules, yet their own culture drives decisions to the contrary. Why? Because everyone treats procedural adherence as a step in a process instead of a behavior motivated by perceived risk.

Many factors impact how employees comply with procedures: company culture, environmental complexities, the quality of existing support systems, and human nature. In this white paper, we’ll break down what drives employees to behave the way they do, so you can recast your organization as one where procedural adherence is the norm.

The Safety Paradox

A popular consensus is that it’s easiest for people to follow safety rules. While a narrow view, it’s useful to illustrate some truths about risk.

The basic reason we enjoy some measure of success with procedural adherence in safety matters is because unsafe behaviors are visible and may result in immediate consequence.

Safety rules tend to be easier to adopt because violations are more visible, and consequences are bad for both the individual and the enterprise.

But there is a more fundamental reason why. Accidents cause personal harm and enterprise disruption. In other words; failure to follow the safety rules can be bad for everyone. This alignment – a mutual understanding of risk – serves to induce a state of better procedural adherence with respect to safety matters.

Safety programs further reinforce these notions by stating that anyone can spot and audit unsafe behaviors and must do so as part of a “safety culture.” Unfortunately, easy-to-observe violations cause only a fraction of all incidents. By contrast, invisible missteps tend to stay buried deep inside complex procedures, only coming to light when something’s gone very wrong.

Given this insight, it’s all the more astounding to realize that, even where it’s clear that procedural non-compliance hurts everyone and rules are explicit, people will still make choices that put themselves and others in harm’s way. When this happens, it tells us a lot about the underlying values of the enterprise and how we all think about and deal with risk.

Two Modes of Thinking Affect Risk Behavior

A procedure is a complex chain of tasks and processes that are linked and sequenced to deliver a product or service to a customer. In that “value chain”, many hands touch and impact deliverables: individuals, functions, departments, service providers, suppliers, partners and so on. Each actor has visibility into their part of the chain, but rarely to the ins and outs of the entire system, nor the potential cascade of consequences that could arise from a misstep.

Mostly, people move through the day doing their job, responding to inputs, and reacting to issues as they arise. Occasionally, there’s a need to divert attention to a more complex problem, but mostly it’s about turning the crank. Immediate surroundings and cultural norms — “the environment” — drive much of their behavior.

Does “get the job done” trump “do the job right” in your organization?

The pressure to perform follows a few main themes: Keep things moving, be efficient, manage costs and assure good quality. No matter what anyone says, or how many DO THE JOB RIGHT posters hang on the walls, job pressure doesn’t necessarily include following the rules. The status quo barks out: Get the job done. In such an environment, going with the flow is perceived as less risky than monitoring and complying with all the procedural requirements. After all, we’re problem-solvers, right? A little rule-bending is expected and condoned.

Thinking Fast and Slow

For all of us, two distinct modes of thinking are constantly in play: fast and slow. Fast thinking is reactive, responsive and automatic. It looks for patterns, gets us through our day and requires little energy. When considering the equation: 2+2, you quickly conclude 4 as the only possible answer. That’s fast thinking.

Slow thinking, on the other hand, is just that: slow. It uses lots of energy because it requires focused attention. You’d need to employ slow thinking to multiply fractions, for instance, or to figure out how to avoid your least favorite relative at the family reunion.

As we fast-think through our day, we’re trying to avoid risk by paying attention to what people around us expect. This is human nature and not much of a conscious decision. Cutting some corners feels reasonable.

At the enterprise level, where policy is made and direction is set, the job IS slow thinking: planning new and better ways of doing things, improving results, satisfying customers and avoiding unpleasant surprises. All of those outcomes seem more likely when people follow the rules, so adhering to standard procedures is viewed as a way to lower risk.

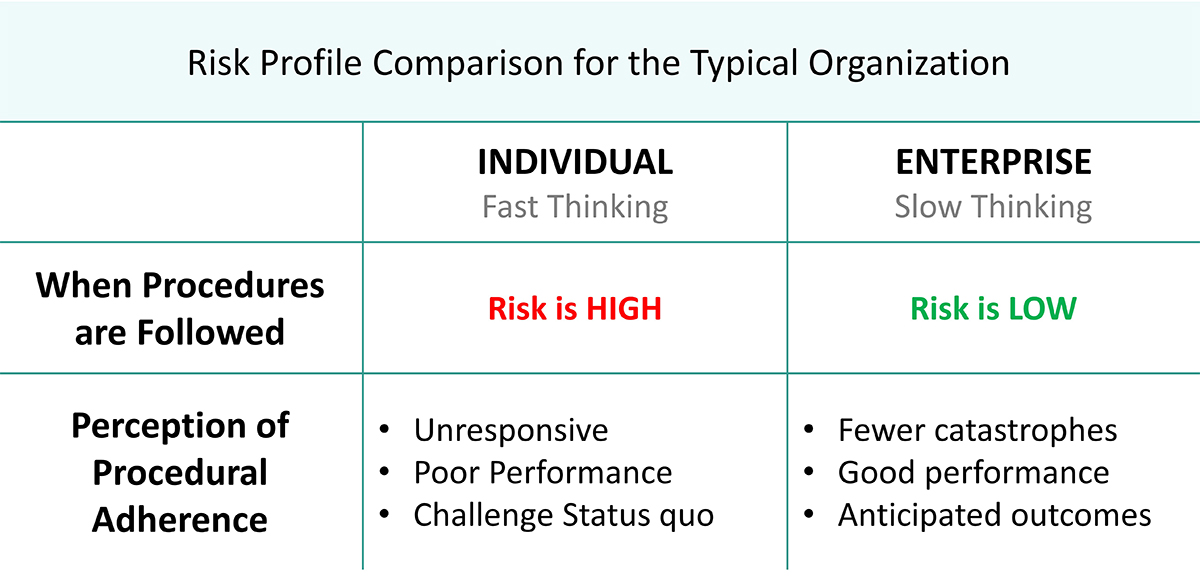

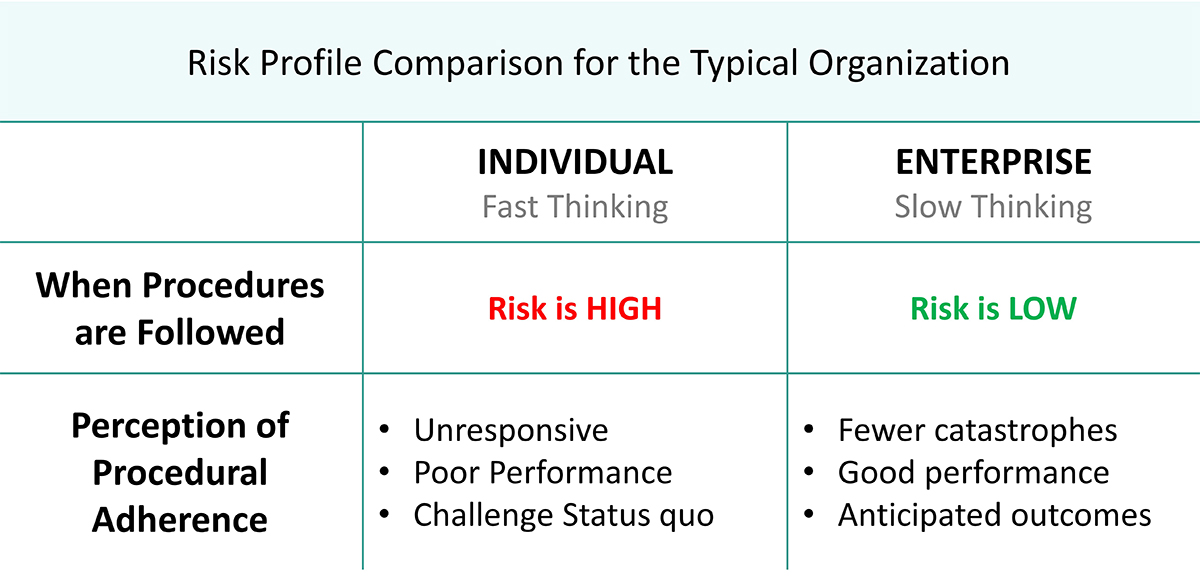

Table 1 – In a traditional organization, following procedures can be viewed as having high or low risk, depending on one’s vantage point.

Table 1 contrasts these dynamics from the point of view of the individual vs. the enterprise. This misalignment between risk perceptions, plus the reactive nature of fast thinking patterns, are the reasons why your organization might be having a hard time achieving better procedural adherence. If rules are routinely broken where you are, it’s because no matter what anyone says, your organization’s true values are to get the job done — even if it means not following procedures.

A caveat: the foregoing assumes that tasks, processes and procedures are well defined, well documented and well understood — which is almost never the case. If you expect compliance but have not made the procedures clear, easily available and understandable, you’re fooling yourself and shortchanging your valuable workforce.

Procedural Adherence and Risk Defined

Given our understanding of how human nature drives or hinders procedural adherence, we can construct a simple definition. Procedural adherence is:

Aligned values and explicit behaviors that demonstrate the highest regard for following established standards to minimize risk.

If we break the definition down piece by piece, these points are important to understand:

- When individuals and the enterprise share the same values, that alignment will translate to observable behaviors. As the saying goes, actions speak louder than words.

- If you expect someone to follow the rules, then you’d better make those rules clear and understandable.

- Adhering to procedures must become low-risk for everyone.

Our definition of procedural adherence goes well beyond the notion of false slogans and checklists to encourage compliance. It provides handles for people to grab ahold of. If we really want better procedural adherence, values must be aligned and why values were not aligned in the first place is the real root cause analysis that must be done.

Start by getting a grip on definitions, documentation and conveyance of the procedures that need to be followed. Focus on the ones that are most vital to the enterprise. Rationalize the list of critical expectations and then ACT on them. This requires active governance (that probably doesn’t currently exist) versus the typical haphazard, “Let’s do everything” approach.

Once you have a solid set of rational procedures that must be followed, react strongly when violations occur and dig for the cultural root cause when they do. You’ll often find the violators felt they were acting in accordance to their bosses’ objectives and in the best interest of the enterprise. Note: There is often a lot of bad precedent to be undone here.

While the conventional approaches to procedural adherence problems – Defining, Training and Discipline – have their place, they could be sabotaging your compliance efforts by looking like progress, but instead are just more of the same.

Targeting Behaviors for Lasting Improvements

We now know your enterprise and the individuals inside it at many times think differently. People on the ground think fast and avoid personal risk by occasionally breaking rules — and if the organizational culture says it’s ok to do it sometimes, it’s ok to do it any time. Conversely, the “think slow” enterprise seeks to minimize risk by getting everyone to follow the rules.

The key is to align the risk profiles for both. It’s the only path that works because it operates at the behavioral level. This requires a direct frontal attack on the status quo — an uncomfortable proposition for most, but one that must be done if real change is desired. After all, we’re talking about replacing poor habits (behaviors) with good ones. This is a goal that can only be accomplished with an approach that is: (a) highly visible, (b) effective in its execution, and (c) simple enough for everyone to understand.

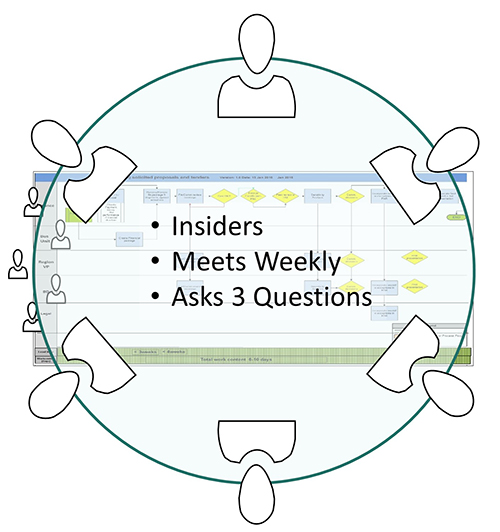

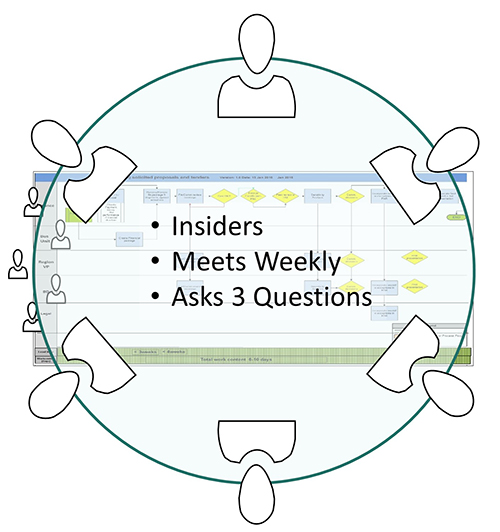

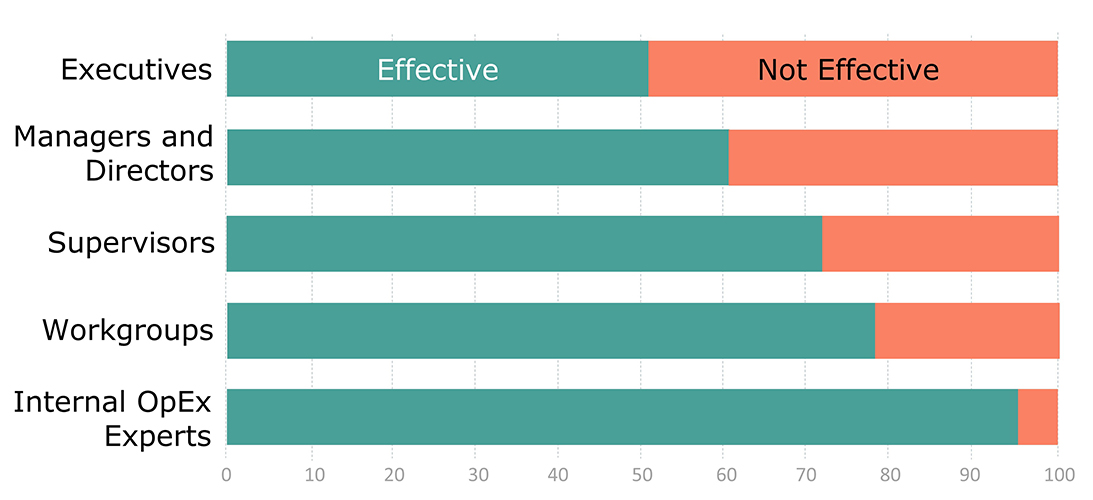

Figure 2 – A high performing FSC provides the organization a leading indicator of procedural adherence.

Our solution — which many high-performance organizations have successfully adopted — is an engaged and visible coalition of leaders whose implicit and explicit objective is to reinforce a set of values with which everyone can align. We call this body the Functional Steering Committee (FSC). FSC participants are directors and functional heads tasked with managing major process nodes along the value chain. They meet weekly and review procedural adherence status by asking three questions:

- Do we have the procedure?

- Do we understand the procedure?

- Are we doing the procedure?

Why meet weekly? In our experience, a weekly cadence is vital. If less, participants lose interest and urgency. Monthly sessions result in a last-minute rush to gloss over subpar progress and shoddy work. This is the very behavior that better procedural adherence is designed to attack. But by tackling issues weekly, communicating expectations, asking the right questions and demonstrating the benefits of procedural adherence, the risk alignment profiles noted in Table 2 become the new status quo.

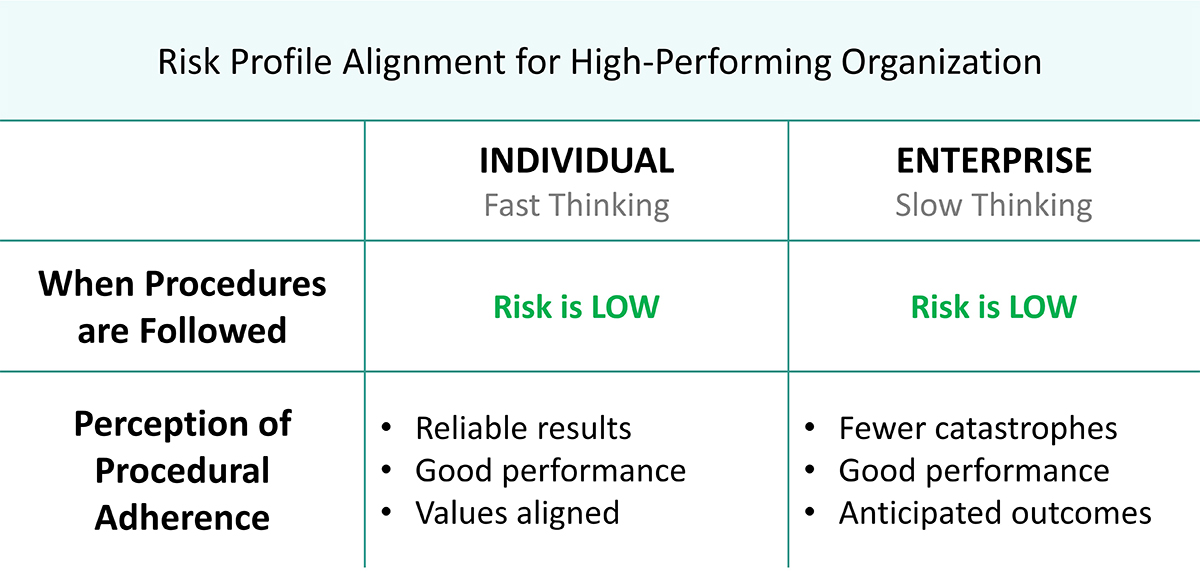

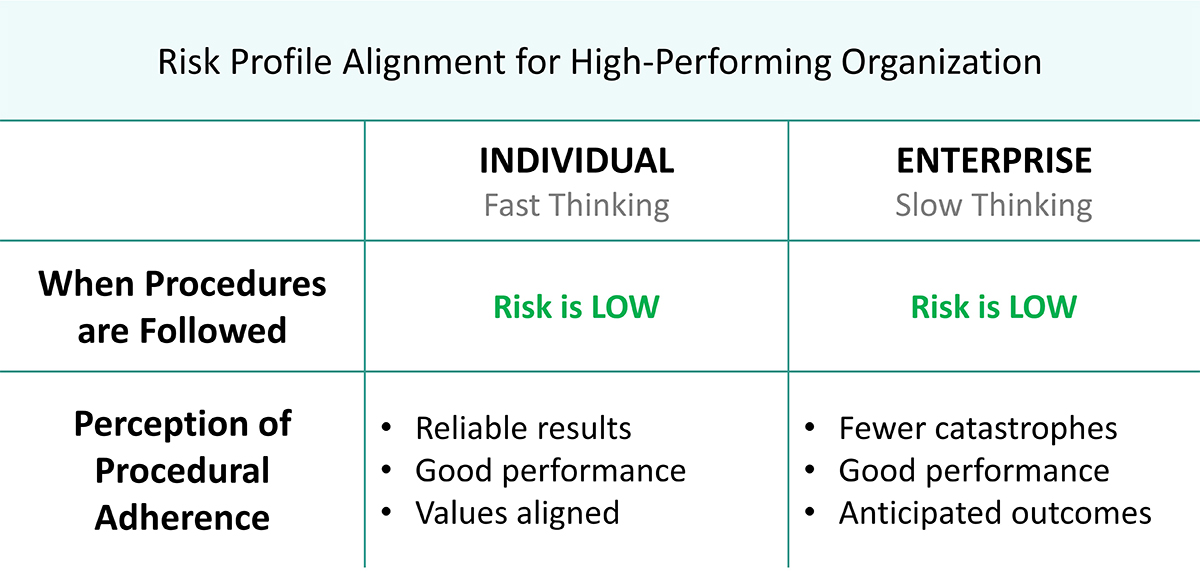

Table 2 – When the risk profiles are the same for the enterprise as the individual, everyone is motivated to act in the same way because the cultural norm is to follow procedures.

The chartered and structured FSC is a new behavior. It’s highly visible and is a leading indicator of better procedural adherence. Over time, the enterprise and individual employees begin valuing the same things, and decisions become more aligned, consistent and mutually beneficial. And, FSC benefits don’t stop here.

The FSC governs the technical aspects of improvement too, pinpointing gaps that might otherwise go unnoticed. For example, if someone does not have a documented procedure, who better to help than the FSC? If there is confusion about how a procedure is supposed to work, the FSC intervenes. If someone isn’t following the rules, the team will find out why and encourage / remove barriers to doing so in real time. The FSC can surface innovations that can then be built into the formal, standard approach.

With respect to procedural adherence, often this governance role is not being done well, or at all. This is a gap that needs to be closed. Yet the usual objections will be heard: “Do we really need another meeting?” and “Can’t we automate this?” Some will suggest that technology is a better answer, or another meeting is too much. Technology can help, especially in the area of standard templates and sharing best practices. Remember, however, that you’re dealing with a behavioral issue. If “just another meeting” seems like too much, eliminate three useless ones or have the FSC integrate the responsibilities of the team that’s investigating the most recent catastrophe.

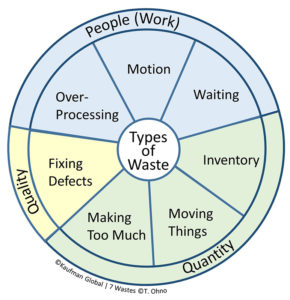

When it comes to procedural adherence and risk, one of the biggest problems your organization will face is getting functions and departments to come together to solve system-level problems like procedural adherence. The solutions to these types of problems: efficiency, effectiveness, productivity, quality and customer-focus are solved using Lean and other process improvement techniques. The first step is gap identification, and this new approach with the FSC is ready-made for that.

A New Destination Requires a New Path

Einstein famously defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over while expecting different results. You’ve likely heard that proverb a dozen times, nodded in agreement, and returned to old practices expecting new outcomes.

Likewise, returning to traditional approaches where procedures are treated like guidelines instead of values-driven standards will result in the level of compliance in your organization remaining unchanged… or inconsistent, at best.

It won’t be easy. Old ways die hard. Your organization will face tough decisions about chasing revenue, be tempted by the notion that a small defect or minor violation won’t matter, and that speed trumps standards. These moments of truth happen every day, swaying people to compromise and make poor choices.

The payoff for doing something truly different, however, is huge. Imagine a 20% reduction in catastrophic events and the benefits when this 20% is spread across all types of incidents. Imagine a team of leaders working across functions, better understanding each other’s needs, and monitoring hand-offs between them. Finally, consider the relief, shot of confidence and productivity for front line workers who know the rules, and no longer feel the pressure to disregard them – instead, operating in an environment that demonstrably values them.

This post is an excerpt from Kaufman Global’s White Paper: Procedural Adherence and Risk. To acquire a copy of the full white paper, click here.

If you’d like to learn more about the services we offer related to addressing Procedural Adherence challenges, click here.

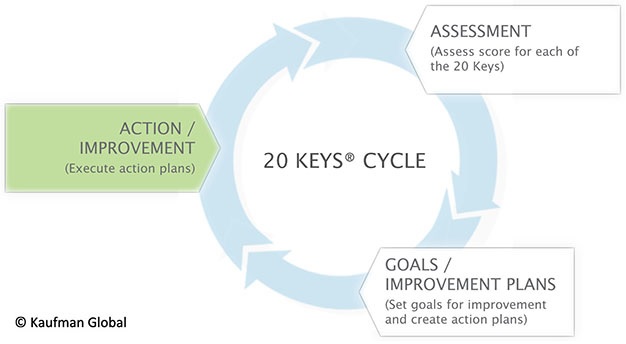

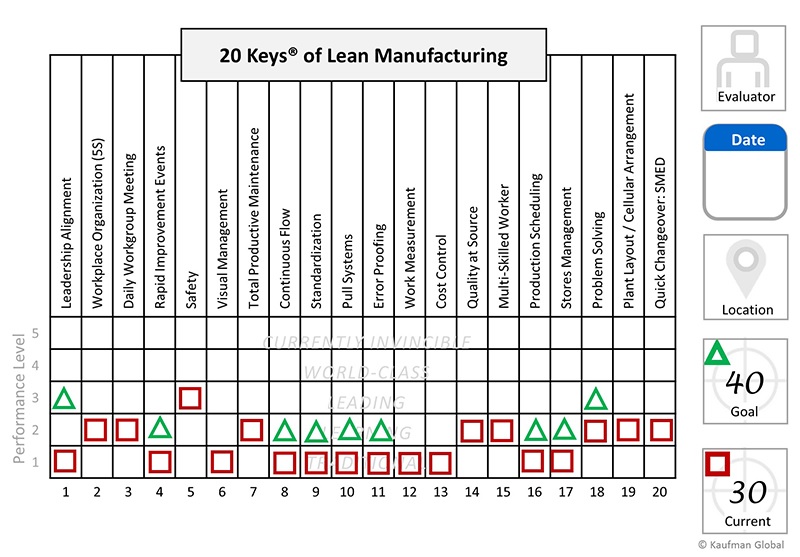

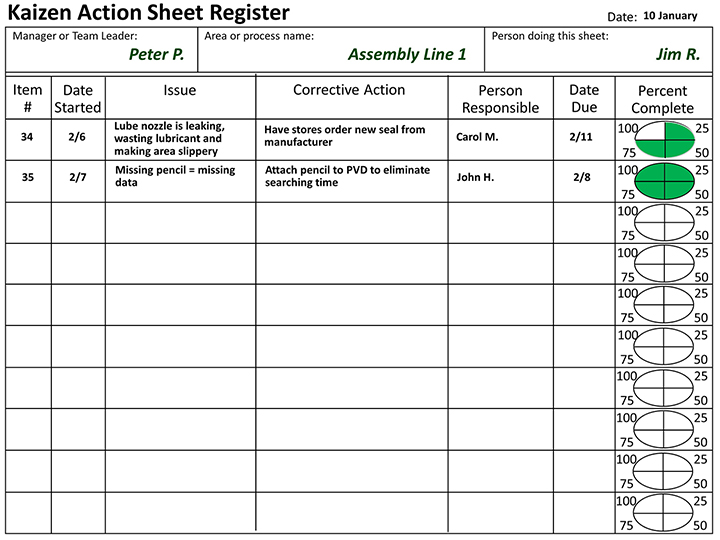

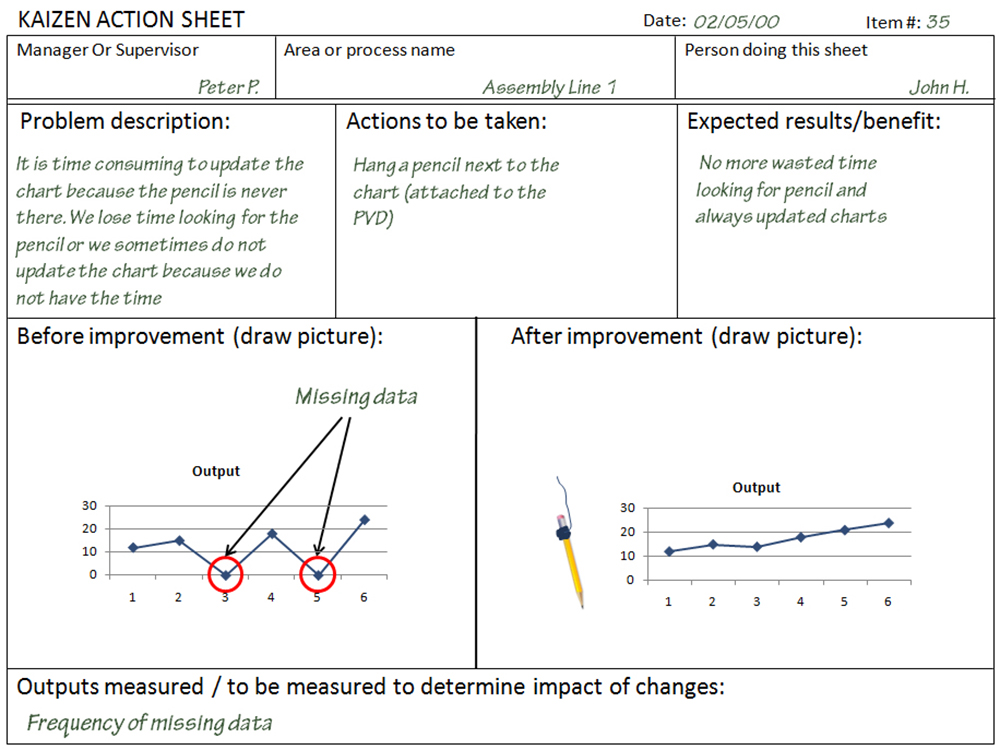

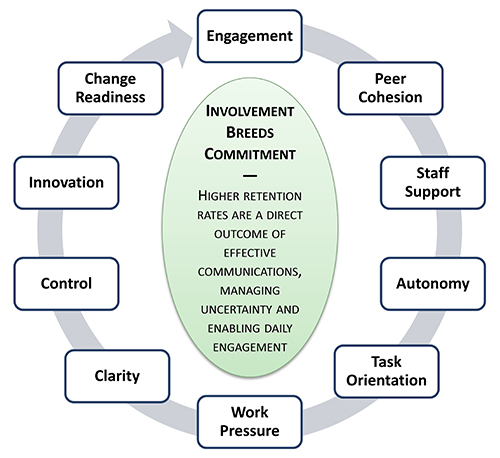

right). Applying the 20 Keys helps individual workgroups evaluate and understand their own performance, then develop a structured long-term improvement plan for their specific situation (20 Keys cycle inset below). While leadership or third-party resources often help with an initial assessment, many believe that the fact that 20 Keys becomes a self-assessment — that is, the keys are evaluated and acted upon by a workgroup who rates and pushes themselves — is likely to be the most important aspect in its success through compelling buy-in and ownership. Moreover, the plain language quality of the keys means that the key’s level-descriptions really can’t be gamed; something simply doesn’t smell right when reality and numbers don’t track.

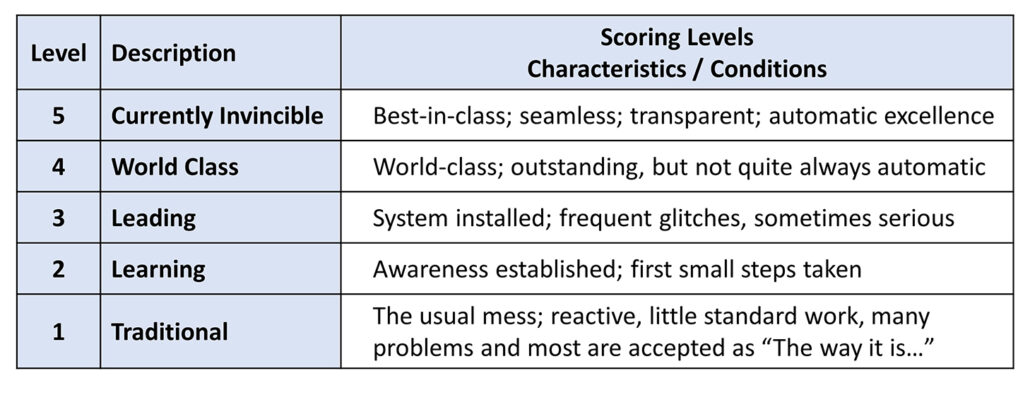

right). Applying the 20 Keys helps individual workgroups evaluate and understand their own performance, then develop a structured long-term improvement plan for their specific situation (20 Keys cycle inset below). While leadership or third-party resources often help with an initial assessment, many believe that the fact that 20 Keys becomes a self-assessment — that is, the keys are evaluated and acted upon by a workgroup who rates and pushes themselves — is likely to be the most important aspect in its success through compelling buy-in and ownership. Moreover, the plain language quality of the keys means that the key’s level-descriptions really can’t be gamed; something simply doesn’t smell right when reality and numbers don’t track. erational or functional work areas (ex.: manufacturing or materials management) in 20 “key” elements (ex.: error-proofing or problem-solving) whose descriptions reflect steps toward world-class performance benchmarks. For each key, five performance ranks are described in plain language beginning with a Level 1 – Traditional through Level 5 – Currently Invincible (table inset below).

erational or functional work areas (ex.: manufacturing or materials management) in 20 “key” elements (ex.: error-proofing or problem-solving) whose descriptions reflect steps toward world-class performance benchmarks. For each key, five performance ranks are described in plain language beginning with a Level 1 – Traditional through Level 5 – Currently Invincible (table inset below). Completed 20 Keys data packs consist of: a chart mapping goal attainment; a corresponding set of point or level descriptors for individual keys; and, a workgroup devised and maintained action plan detailing who does what by when in order to achieve workgroup improvement aims. Overall, a starting point is no less than 20 points (1 point earned for “traditional” in each key) and 100 points is the maximum achievable. Improving 10 points per year in early years is doable. Workgroups having achieved 60 points tend to look and feel fantastic and are quite high-functioning. Although it can happen, we don’t encounter many workgroups over the low 80s.

Completed 20 Keys data packs consist of: a chart mapping goal attainment; a corresponding set of point or level descriptors for individual keys; and, a workgroup devised and maintained action plan detailing who does what by when in order to achieve workgroup improvement aims. Overall, a starting point is no less than 20 points (1 point earned for “traditional” in each key) and 100 points is the maximum achievable. Improving 10 points per year in early years is doable. Workgroups having achieved 60 points tend to look and feel fantastic and are quite high-functioning. Although it can happen, we don’t encounter many workgroups over the low 80s. In order to level-set, monitor and review continuous improvement progress, there’s no better approach than Kaufman Global’s 20 Keys®, a proprietary method focusing intact workgroups on the vital dimensions of how it operates versus world-class benchmarks. Transcending both language and culture, organizations worldwide have implemented 20 Keys with sustained success. Kaufman Global has developed over 25 different sets of keys applicable to operational and functional settings, including Customer Service, Supply Chain Management, Engineering and Project Management. Regardless of which sets are used, 20 Keys relays a standard approach to evaluate and improve performance effectiveness throughout your enterprise.

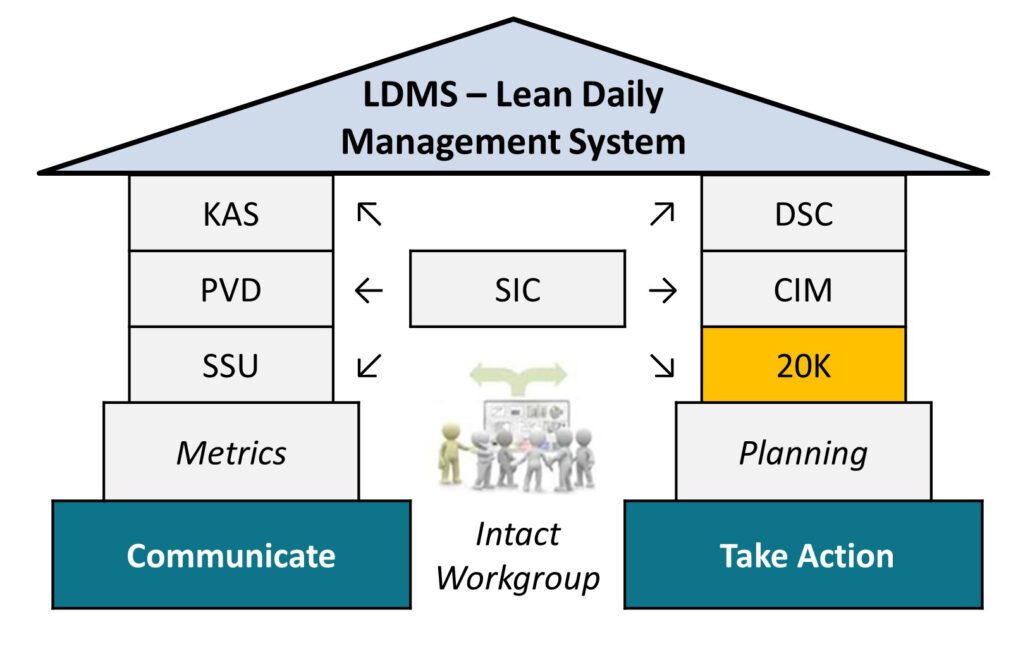

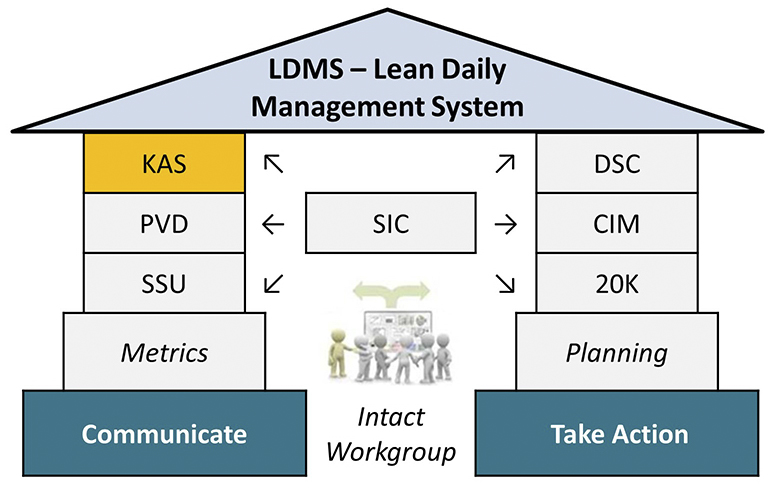

In order to level-set, monitor and review continuous improvement progress, there’s no better approach than Kaufman Global’s 20 Keys®, a proprietary method focusing intact workgroups on the vital dimensions of how it operates versus world-class benchmarks. Transcending both language and culture, organizations worldwide have implemented 20 Keys with sustained success. Kaufman Global has developed over 25 different sets of keys applicable to operational and functional settings, including Customer Service, Supply Chain Management, Engineering and Project Management. Regardless of which sets are used, 20 Keys relays a standard approach to evaluate and improve performance effectiveness throughout your enterprise. Description: Within the context of the Lean Daily Management System (see inset at right), the

Description: Within the context of the Lean Daily Management System (see inset at right), the

Supplemental Reading Recommendation:

Supplemental Reading Recommendation: